Choosing a Telescope |

|

There is no "best" telescope for everyone. The one that’s right for you will depend on your lifestyle and your astronomy goals. The best telescope is the one you’ll use most often. And that will depend on your comfort zone in terms of size, price and ease of use.

There are 3 basic types of telescopes:

1. Refractors are long, thin telescopes that collect light through multi-element lenses. Known for sharp, detailed, contrasty images, they are best for viewing the moon and planets.

2. Reflectors (Newtonian) collect light with a curved, concave mirror. Their large apertures allow them to serve up fine, highly-resolved images of planets and deep-sky objects alike. These scopes are unsuitable for terrestrial (earthly) viewing as they produce an upside-down image and are designed exclusively for astronomy.

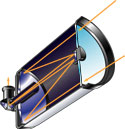

3. Catadioptrics or compound telescopes (Schmidt-Cassegrain or Maksutov-Cassegrain) use both mirrors and lenses to collect and focus the incoming light. They sport very compact tubes, and give you great all-around performance.

|

|

|

|

Refractor

|

Reflector

|

Catadioptric

|

Aperture vs Magnification

All telescopes collect and focus light. The most important feature of any telescope is its light gathering capability, or aperture (the diameter of the main lens or mirror, usually expressed in inches or millimeters) that determines how much you will be able to see. The more light gathered, the more you’ll see. For example, a 6" mirror/lens is 2-1/2 times the diameter of a 60mm mirror/lens, yet it gathers 5-1/2 times more light. The brightness-boost delivered by the bigger, high-quality optics seems to yield dramatically finer detail, simply because previously invisible structure gets promoted to the visible~or in other words, the resolving power is increased.

Large apertures (more than 8") will yield sharper images only when that area’s stable atmospheric conditions (primarily air turbulence) promotes excellent "seeing". Most of the time in most of the world, seeing is moderate to poor. Magnification is not the most important consideration when choosing a telescope. Telescopes advertised on the basis of high magnification (400X to 575X power, or more) are a sure sign of inferior quality. Excessive magnification blurs the already blurry image, mostly by amplifying the effects of air turbulence. In practice, 300X is about the maximum. The brightest and sharpest images are obtained from much lower powers, on the order of 30X to 50X. The telescope's power or magnification is adjusted by changing eyepieces. How many eyepieces should you have? Three is ideal~one low, one medium and one high magnification. The lower its number, the greater the magnification. For a larger image, use an eyepiece with a larger number (i.e., 20mm). For close-ups, use a smaller number (i.e., 4mm). You can buy other eyepieces to increase the versatility of your telescope, or you may want to purchase a Barlow 2X lens that is inserted into the focusing tube before the eyepiece which doubles the magnification~a good way of getting double the performance out of each eyepiece! Apart from making the image of the subject larger or smaller, magnification has a bearing on the area of sky (termed the field of view) you will see~higher magnifications have smaller fields of view, which can make finding objects that much more difficult.

Generally speaking, lower powers of 30 - 50X are advisable for observing star clusters, galaxies and nebulae since they are often spread over a wide area of sky. Medium powers of 80 - 100X are convenient for studying the craters and valleys of the Moon's surface, seeing the rings of Saturn, or Jupiter and its four principal moons. Higher powers of 150 - 200X will permit you to scrutinize mountain peaks and fine lunar detail, the surface features of Mars or to separate close double stars. Here is the formula for computing the magnifying power of your telescope:

|

Focal Length of Telescope |

|

|

|

divided by |

= | Magnifiying Power |

|

Focal

Length of Eyepiece

|

- or -

|

1000mm divided by 20mm |

=

|

50X |

(example)

Focal lengths are expressed in millimeters. You will find the focal length of the eyepiece printed on the eyepiece itself and the focal length of the telescope printed on the telescope assembly tube itself or in the manual.

Telescope Mounts

A quick word about telescope mounts. Telescopes come on three basic mounts: altazimuth, Dobsonian, or equatorial. The altazimuth is the simplest type of mount, providing up-down, left-right motions and is recommended for casual stargazing and terrestrial viewing. The Dobsonian mount is a boxy altaz-type mount that sits close to the ground and was designed for easy maneuvering of large reflectors or Newtonian tubes of 6" or greater. Equatorial mounts are a bit more complicated (and more expensive) than the altazimuth mounts and are designed solely for astronomical viewing. They are tilted, with one axis aligned on the celestial pole. These type of mounts allow the user to track or follow the motion of celestial objects through the sky with a single manual hand control, or automatically with a motor drive~a great convenience. Most telescopes come with a sturdy mount and a tripod to bring the eyepiece up to eye level, (beware of "tabletop" telescopes that look cute in ads but require an expensive, optional tripod to be practical).

Refractors

For observing the Moon and major planets and separating out binary stars~a small, quality achromatic refractor of 60mm to 80mm aperture will make a fine starter scope. They are portable, maintenance free, and inexpensive ($100 - $400). Moving up to a 90mm or 100mm aperture will snare more objects and provide better performance, for a higher price. Renowned for their crisp, sharp, contrasty images~refractors are the priciest per inch of aperture of all the scopes. Their cost and bulk factors limit the practical useful maximum size to smaller apertures. A refractor is the scope of choice if you will be doing most of your observing from the city or suburbs, where the night skies are moderately light-polluted. Here, more aperture doesn’t gain you much, since viewing is restricted to the Moon and planets. A big scope would only amplify the skyglow, yielding poor washed out images.

Reflectors

Newtonian reflectors are great all-around scopes, offering generous apertures at affordable prices. They work for both planetary and deep-sky viewing. These scopes are more fragile and require more maintenance than the others. An open optical tube design allows image-degrading air currents and air contaminants, which over time will degrade the mirror coatings and decrease performance. The optical components can go out of alignment, requiring collimating. Of course, the larger the aperture, the more you’ll see. Smaller 3" and 4.5" equatorially mounted Newtonians will provide a nice survey of celestial luminaries, and they are easily portable. 6" and 8" Newts have enough aperture to deliver captivating images of fainter fare~clusters, galaxies and nebulas, especially in a reasonably dark sky. The trade off is their bulk and weight~something you should definitely take into consideration. But a 6" Newtonian on a Dobsonian mount is easily manageable by one person and makes a great starter scope. Dobsonian-mounted reflectors are lower in price than their equatorial counterparts and start around $350.

Catadioptrics

These scopes are the most versatile telescopes and have the best all around, all purpose design. The Schmidt-Cassegrain or Maksutov-Cassegrain scopes are very portable. They utilize a large aperture in a very compact tube. Away from urban sprawl, with reasonably dark skies, an 8" SC provides excellent views of the Moon, planets, and faint deep-sky objects (clusters, galaxies, nebulas, comets etc.) and is well suited for astrophotography. You will pay over $1000 for the most basic models (and hundreds more to outfit it for astrophotography) with an equatorial mount. With a hefty tripod and mount, the larger models (10" & 12") can be a bit cumbersome for one person. There are more accessories available for these scopes than the other two. These telescopes are gaining popularity and can be completely computer-controlled, giving it what‘s called "GO TO" capability to any object in the sky, if you want to pay the price. They start at $1700.

|

|

|

|

|

Refractor

on

Equatorial mount |

Newtonian

reflector

on Equatorial mount |

Schmidt-Cassegrain

on Equatorial mount |

Newtonian

reflector

on Dobsonian mount |

More on GO TO Catadioptric Telescopes

A new telescope and a crystal-clear dark sky … what more could the amateur astronomer want? But often the outcome is frustration when it proves difficult to find stars, planets or other astral objects in the lens.

The positions of objects in the sky are pinpointed using the sky’s equivalent of longitude and latitude, called right ascension and declination. Equatorial-type telescope mountings have dials, called setting circles, that carry these scales. The problem is, that because of the Earth’s daily rotation, the direction of a given right ascension is changing all the time and the direction of a given declination depends on the location of the telescope on Earth. Before an equatorial mounting can be used, it must be aligned so that one axis is exactly parallel with the Earth’s axis, which takes time and care. Then the setting circles must be set up for that particular time of observation. This must be repeated each time you set up the telescope. Many people with portable instruments prefer to find objects by star-hopping, but if you do not know the night sky very well, this can be difficult as well. Even aligning the spotting scope with the main scope can get a bit meticulous at times.

There are now computer-controlled mountings which do away with all this fiddling. These mountings have optical encoders on their axes, which give a digital readout of which direction the telescope is pointing. They are also equipped with purpose-built computerized handsets that are pre-programmed with the positions of thousands of celestial objects.

To find an object, all the user has to do is to be able to recognize two bright stars in the sky. The telescope is pointed at each one in turn, and the identity of the star is entered on the handset. Since any two stars are in unique directions at a given time and place on earth, the computer can work out the position of any other object in the sky and will move the telescope to it on command. To find a planet, you have to key in the date as well. A computerized mounting does not even need to be aligned with the Earth’s axis. It will track a chosen object even if it is not equatorially mounted, although this is still necessary for taking long-exposure photographs.

|

Helpful Tips If you wear glasses, you do not normally need them when looking through a telescope. Only people diagnosed with a bad astigmatism may need to use their glasses. Never directly observe the Sun with a telescope without the proper filter. It is harmful to your eyes. |

- David D. Chittenden III

Astronomy

Resources

Compilation of valuable links on stargazing, meteorology, educational

and job resources

Space

and Science: An Online Study Guide for Kids

Resources on the planets, stars, telescopes and eclipses

|

Thank You for Your Heartfelt |

Rocks

Earthly Delights

The Night Sky

Mysteries of the Universe

Legendary Journeys of Hercules

Cosomolgy

Linkups~SouledOut.org's Recommended Links

Glossary of Esoteric Terms & Phrases

SouledOut.org Site Map

SouledOut.org Home